Where there is a monster, there is a miracle – Ogden Nash

I’ve always liked that quote. I like quotes in general, but that one I like because it a) is about monsters, and I have a fondness for monsters and b) it doesn’t assume that monstrosity is a negative thing.

Monsters have always had a poor reputation. Telling someone that they are a ‘monster’ is shorthand for proclaiming that they are a vile, evil, nasty swine, so awful they can’t reasonably lay claim to being human. In some instances it’s probably justified, but I’m not here to write about real-life monsters. My interest is in the monsters that can be found in the pages of novels, on the silver and small screens, in art and just about anywhere within pop culture.

Monsters have existed ever since humankind began telling stories. There’s the Minotaur and the Hydra of Ancient Greek Myth, Anzû and Asag in Mesopotamian religions (the former so hideous that its mere presence can boil fish alive in rivers), the Barghest or Black Dog of Northern England. Iconic monsters such as the vampire, the werewolf (my personal favourite), Frankenstein’s Creature, the Gill-Man of The Creature From the Black Lagoon and even King Kong and Godzilla are continually being reimagined for new films and TV series. The internet has given us the concept of creepypasta and the already iconic Slender Man. There are thousands upon thousands of monsters, all of them unique, exceptional, remarkable.

When writing about ugliness, Umberto Eco states that ‘beauty is finite, ugliness is infinite like God.’ He explains that a beautiful thing must always follow certain rules: it can’t be too much of this, or too little of that, or too big/small/wide/narrow/tall/short (insert appropriate adjective here). But ugliness is infinite. There are innumerable ways to be ugly. And there are innumerable ways in which to be or become a monster. On this blog, I’m planning to study and analyse different monsters, mostly for my own enjoyment but hopefully for yours too.

So, where to start? With a book, a film, an urban legend? With a monster as iconic as Dracula, or as obscure as the Beast of Dean? (The latter is a giant boar, by the way). Should I proceed chronologically, alphabetically, by geographical region, stick a bunch of monster names in my top hat and pick one? There’s almost too much to choose from. But there is one consistent characteristic of the truly iconic monsters: they belong in the past.

Allow me to elucidate: many moons ago, I attended an academic conference that focused on monsters and the Gothic. Each morning and afternoon, I attended a panel that consisted of three people presenting twenty minute papers on topics centred round a particular theme. One of the papers contained the suggestion that iconic monsters all belong to the past – we have lost the ability to create exemplary creatures, that instantly pass into popular legend. Say ‘Dracula’ to someone, and even if they’ve never read the book or seen a vampire film all the way through, it’s more than likely they’ll have at least have heard of Dracula. It would be the same with Frankenstein’s Creature, or a werewolf, or Godzilla, or Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. None of these monsters, however, emerged in the twenty-first century. Out of all of them Godzilla is the baby, having first appeared in film in 1954, making him 70 years old this year. Dracula and Frankenstein were written in the nineteenth century, albeit at opposite ends (Frankenstein was first published in 1818, Dracula in 1897) and the werewolf is an ancient monster, making appearances in Greek myth and the Epic of Gilgamesh (the earliest parts of which may have been composed around 2,100 BC). While the vampire and the werewolf are constantly being reinvented, what about the new monsters? Those created in and around the millennium?

Well, they’re not terribly impressive – either that or they haven’t managed to attain legendary status. The Blair Witch Project (1999) created a fabulous mythology surrounding the eponymous witch but never allowed the audience to catch a glimpse of her. Whilst a brilliant narrative device, it doesn’t allow for the creation of a new monster in the public consciousness. We learn about the witch, we know she’s lurking in the dark just off camera, but we are never permitted to see her, to allow her shape to take root in our imaginations.

Perhaps the greatest monster maker of the late twentieth/ early twenty-first century, Guillermo del Toro, has done monster lovers everywhere proud with his creations. He’s realised dozens of grotesque, brilliant imaginings on the cinema screen. Out of all his creations, surely the greatest is the Pale Man from Pan’s Labyrinth or El laberinto del fauno in the original Spanish (2006).

The child-eating Pale Man.

The Pale Man is utterly grotesque. His spindly limbs and sagging skin suggest starvation, but the banquet set before him and the paintings surrounding him – all depicting him devouring children – together with a massive pile of children’s shoes, reveal his gluttonous, insatiable nature. Watching him chase the film’s protagonist, Ofelia, and knowing the horrible fate that awaited her if he caught her, was utterly terrifying. It was the most frightened I’ve ever been in the cinema (and I’m a horror film fan, so it’s not like I’m unused to fearful scenarios). Even horror maestro Stephen King, when confronted with the Pale Man, squirmed like crazy in his cinema seat (according to Del Toro, who was sat next to him. He noted that it was one of the proudest moments of his career, equivalent to winning an Oscar).

But the Pale Man has not become (almost) universally recognised as Frankenstein’s Creature has, for instance. I believe this is partly because Pan’s Labyrinth is a Spanish language film, and in our Anglophonic world, that is a notable disadvantage when trying to reach the broadest possible audience. Also, perhaps the Pale Man is simply too weird to be a truly mainstream monster (although the iconic monsters listed above were no doubt considered just as weird when they made their debut).

Perhaps all the truly great monsters do belong in the past. Are we doomed to go forth into a world without monsters? I sincerely hope not. And there is hope, though perhaps not in the places we are accustomed to look for it. Have you ever heard the term creepypasta? A corruption of the computer command ‘copy and paste,’ a simple definition of this is an urban legend, usually horror based that is disseminated via the internet rather than by word of mouth. Examples include Candle Cove, Jeff the Killer, the Russian Sleep Experiment, the Rake and, the prime example, Slender Man.

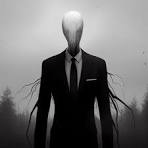

The infamous Slender Man

Slender Man originated on the Something Awful forum in two edited photographs and a paragraph or two that hinted at tragedy. From there, he’s appeared in art, video games, a film and countless online memes and stories. Disturbingly, readers of his fiction have been connected to several violent acts, particularly a near-fatal stabbing of a girl in Wisconsin in 2012. Such violence is reprehensible, I definitely don’t want to condone it. And it led to a decline in Slender Man’s almost meteoric popularity. What had been a fun, creepy inspiration became something much darker and realer, horrifying many. But for a few years, Slender Man was a modern folk legend, a bogeyman born on the internet. There are great monsters out there still, waiting to be discovered, created or manifested.

Let’s go and explore them. But until then, dear reader, sleep well.

Don’t go out alone.

Leave a comment